Awesome Women Ming Ho

Ming Ho is a writer for Television and Radio with a rolling list of credits for major television series such as Eastenders, Casualty and Heartbeat.

Over the years, Ming has become recognised not only for her prestigious writing talents but her campaigning for causes and issues affecting carers, a role she took on after her mother was diagnosed with dementia. Understandably, this diagnosis had a profound impact on Ming’s life and her writings, evidenced in her moving radio drama, The Things We Never Said, which was aired on Radio 4 earlier this year and has recently been nominated as the Best Radio Drama in the Writers’ Guild Awards 2018.

Having embraced drama and writing from a very young age – writing plays, poems and appearing in local performances, including a production of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat with Anthony Head (everyone’s favourite librarian from Buffy the Vampire Slayer) – Ming imagined she would “launch into the unknown as a freelance creative”, a route that, though unknown, is a typically linear rite of passage for most creatives. But after Ming’s father died of cancer shortly before her finals, she felt the need to get a more stable day job, she says, “As an only child, it was the beginning of my journey supporting my mum, rather than focusing on my own goals and independence.” We spoke to Ming about how she has achieved so much despite dedicating a large portion of her life to caring for her mother, how her life caring for her mother has influenced her work, and her advice to anyone in a similar position.

Could you tell us how you started out in Television?

I moved to London and enrolled on a crash secretarial course – in those days the accepted route (for women) into media jobs. Back then, no-one had a laptop, so I needed to learn “word-processing”, but I was a pretty crap typist (still am!), so those BBC temping jobs never materialised. I did, however, start to read scripts for fringe theatres and got my first job as assistant to a literary agent. It was here that I began to learn about the development process, through reading our clients’ work and seeing how their commissions progressed. While I found this interesting, I knew that agency wasn’t for me in the long term; I wanted to be at the production end, so I became a freelance reader for various film and TV companies and was offered a post at Zenith Productions - at that time a major independent, which had produced feature films such as Wish You Were Here and the long-running Inspector Morse for TV.

As Script Executive, I worked across an extensive slate of film and TV drama (luxuriously development-funded by today’s standards!), and script edited series such as Hamish Macbeth (starring Robert Carlyle) for BBC1 and Bodyguards for ITV. At the end of the ‘90s, I went freelance, co-creating a series, McCready and Daughter, for Ecosse/BBC, and embarked on the scriptwriting phase of my career, via the EastEnders Shadow Scheme. I became a contract writer on the show, working on storylines such as the domestic abuse of Little Mo Morgan by husband Trevor. I went on to write for Casualty, Heartbeat, and The Bill; but my mum had started to develop dementia, and from the mid-2000s her symptoms came to the fore. I had gone freelance partly in anticipation of needing to support her more as she got older, but dementia was an unknown factor (she remained undiagnosed until she went into residential care in 2011), and I had no idea how all-consuming it would become.

I became a contract writer on the show [EastEnders], working on storylines such as the domestic abuse of Little Mo Morgan by husband Trevor. I went on to write for Casualty, Heartbeat, and The Bill; but my mum had started to develop dementia, and from the mid-2000s her symptoms came to the fore.

So although I never consciously withdrew from writing TV, and continued to be involved in the media world through serving on Writers’ Guild committees, negotiating teams, and as Deputy Chair from 2012-14, I fell out of circulation on those long-running dramas. It’s only since mum has been in care that I have been able to focus on my own work again, and have returned to the industry with a focus on original work for stage, screen, and radio.

Could you tell us what your experience as a woman within the industry has been, and whether your experience as a woman in the industry has changed at all over the years?

When I started out, I wasn’t aware of being “a woman in the industry”, as such. My parents had brought me up to believe I could do anything, and from the age of 11 I had attended high-achieving single-sex schools; my university college had (remarkably for the time) been 50/50 gender equal. So I didn’t particularly expect or notice discrimination or inequality on a personal level. You might say that assumption about the woman’s route into media being secretarial was significant. When I looked at powerful TV women of the 80s and 90s, most of them had indeed started out as production secretaries or temps, or maybe as floor managers or ADs who had come from theatre stage management. Young men, it might be argued, were more likely to go straight in as a researcher or formal production trainee. I recall a woman, when asked for advice, saying, “Don’t learn to type, you’ll get stuck as a secretary”. Friends who were PAs, however, have gone on to lucrative careers as production co-ordinators and managers on international blockbusters and are always in demand, so maybe she was wrong!

I think as a young woman looking for early breaks, there’s probably no discernible disadvantage. Where the difference emerges, in my experience, is mid-career (and this is backed up by studies): it’s from your 30s onwards, when caring responsibilities kick in (whether for young children, elderly relatives, or maybe a partner), that it’s harder for women to hold their own and push forward in a highly competitive market place, where networking and pitching for the next job is so important. It’s not just about the actual work on the page, it’s the politics and visibility surrounding the work.

Of course some men do share childcare or support older relatives, but it’s still relatively rare for a man to be a sole carer, as I have been for the last decade or more, which entails putting the person you care for first. The role of ongoing low-level domestic support in enabling career progress should not be underestimated – when you’re working overnight on a deadline, it helps to have someone else to do the shopping, cooking, cleaning, admin, put the bins out, get the car serviced etc, and not to have another person solely dependent on you to keep them alive and functioning.

Looking back at my time in development, I was the only woman in a team with three (older) men and was not as bullish for my own advancement as I should have been. Young men who passed through the company were instantly looking for promotion – and got it, despite having no more experience than me and often less. It’s a classic illustration of the trope that women often wait to be fully qualified for a job before applying, while the equivalent man will wing it on about 60%. I stayed too long in that post and should have been bolder.

Looking back at my time in development, I was the only woman in a team with three (older) men and was not as bullish for my own advancement as I should have been. It’s a classic illustration of the trope that women often wait to be fully qualified for a job before applying, while the equivalent man will wing it on about 60%. I stayed too long in that post and should have been bolder.

I am also rather ashamed now that I didn’t do more at that time to champion women writers. I did work on one show written by a woman (and with a wonderful woman producer) and had female writers in for conversations, but the scripts we commissioned for development were overwhelmingly by men, which reflected both the tastes and networks of my colleagues and prevailing assumptions about the market. There were a number of strong female writers coming through, but their work was mainly in the perceived-to-be “soft” areas of soap and popular nine o’clock series, such as Peak Practice and Soldier, Soldier (hugely successful shows, created by the estimable Lucy Gannon!), and therefore wasn’t reckoned to have as much currency as a masculine thriller or state of the nation piece by a film or theatre name (who was also more likely to be male). Today, we can see that some of those women were Kay Mellor, Sally Wainwright, and Heidi Thomas!

That said, it might have been different if we had been a broadcaster, with direct production commissions to hand out; as an indie, we were pitching short-form series and serials to the BBC and ITV (the only markets back then), so we developed projects we thought had the best chance of being sold.

Looking back at my younger self, I wasn’t conscious of the bigger picture of gender politics and did not yet have the life experience to put it into context. What would I give now for the luxury of that development budget and an expense account to go out trawling for talent! (We didn’t have social media then, which now provides much more direct access in both directions.) Twenty years later, there are more female commissioners and executives, but this has not necessarily resulted in more women freelancers being hired in key roles or on high-end shows. The reasons for this are complex, but arguably amount to a higher degree of prestige still being attached to male “names” above the line.

Looking back at my younger self, I wasn’t conscious of the bigger picture of gender politics and did not yet have the life experience to put it into context. What would I give now for the luxury of that development budget and an expense account to go out trawling for talent!

And while there are more women visible in production in general, female writers (bar a handful of star names) remain largely concentrated in soap and children’s (where in fact a lot of great work is done, but under-appreciated in public). The epithet “soapy” is often used by critics to denigrate a story, but what does it mean? Drama that focuses on character and relationships, rather than action? What’s wrong with that?

I think the “writers’ room” also favours a more combative (or at least assertive) personality with sharp elbows and a strong sense of office politics (none of which is intrinsic to writing talent), so this may be another reason why women find it harder to break out from long-runners into the high-end commissions.

What you think can be done to help equalise diversity within the creative landscape (and everywhere else)? Are things changing? Or is just a lot of it talk?

Things are changing incrementally, notably at entry level; but unless they change as much for (white) men as for women (and BAME, LGBT, those with disabilities), there will always be some disparity beyond middle-age and mid-career. Statutory changes within wider society, such as the legal right to parental leave, childcare, and HR procedures, are much harder to apply to isolated freelancers than to salaried staff; freelancers are always more vulnerable to disadvantage and exploitation - collective representation through organisations and unions, such as the WGGB, Directors UK, BECTU, Equity, NUJ, MU is vital.

The prevalence of unpaid internships – and indeed of unpaid trials and work up front for experienced professionals – obviously hampers diversity, by putting creative careers out of reach to anyone who cannot support themselves without income.

The prevalence of unpaid internships – and indeed of unpaid trials and work up front for experienced professionals – obviously hampers diversity, by putting creative careers out of reach to anyone who cannot support themselves without income. This really needs to be addressed. If it’s worth doing, it’s worth paying for, and if you haven’t budgeted for it, you shouldn’t be in business. (One might sympathise with small start-ups, where everyone is working collectively and for equal penury, but big, established companies have no excuse.)

In recent years, there has been a proliferation of competitions and schemes, mostly for first-timers. While these can be great for launching stellar careers, they leave the vast majority undiscovered – and arguably tend to favour certain types of work, more likely to jump out at a twenty-two-year-old first-round reader. The quietly truthful or slow burner may be overlooked. What happened to just reading people’s work, asking them in for a meeting, and offering them a (properly paid) job?

How has your work caring for your mother influenced your creatively, and equally how it has influenced your working practice -- how you have adapted?

Supporting my mum to live with dementia for up to twenty years now has had a major impact on my life and work. It was a key factor in the decision to leave development/production and go freelance as a writer, which has proven both a plus (flexibility) and a minus (stability, visibility, and income); it’s effectively wiped out ten years of career progression, income, savings, pension, status - I could go on! I’ve written about this in more detail for Media Parents (and on my own blog, Dementia Just Ain’t Sexy).

I started my blog after mum went into care and found it liberating in terms of being able to write exactly what I want, when I want, and to publish it with no third party intervention. It generates no income (I have never sought advertising or sponsorship, because it’s a very occasional blog, and I wanted to retain complete independence of content), but it has brought me many interesting contacts and opportunities in the social care world. I now speak at conferences and events to raise awareness of dementia and carer issues (also unpaid, mostly, which is a moot point in an area where most participants are salaried professionals attending as part of their job or consultants promoting their business); and I’m extensively involved in campaigning work, media, and policy consultations in this field. I’d say it has given me a more mature and rounded view of the world.

Returning to drama, I’ve felt the need to pursue projects that are meaningful to me and allow me a degree of autonomy, even if that means less regular income than on long-running series; and having come to scriptwriting via development, I wanted to find my own voice.

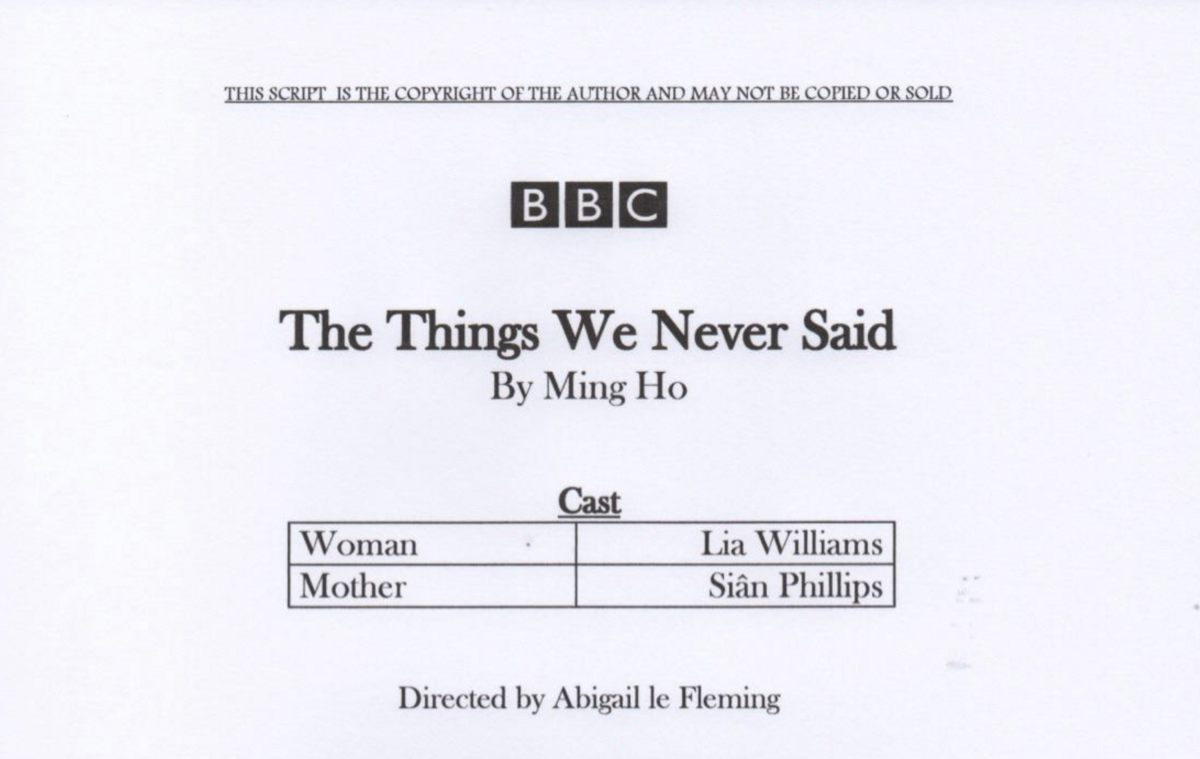

I was selected for the Royal Court Theatre’s first Writers’ Group for those over 26 (formerly “Young Writers”), and my play, Exhumation, was workshopped in-house there in 2015, directed by Associate Director, Lucy Morrison, with cast including Anna Calder-Marshall. It drew on experiences with my mum, but fell between two stools of naturalism and the abstract. After feedback, I decided to be bolder in exploration of the mother/daughter relationship, and wrote a second play, The Things We Never Said, which was produced this year (May 2017) for BBC Radio 4, starring Lia Williams and Siân Phillips. The audience reaction was phenomenal (see Storify for more on that) and I am hoping for a full stage production in future.

A spec story pitch also won me an invitation from French screenwriting organisation, Maison des Scénaristes, to attend their International Screenwriters’ Pavilion at Cannes 2015, and I gained a place on the Bird’s Eye View/BFI/Creative Skillset Filmonomics scheme 2016.

This summer I’ve enjoyed writing Schlaf Nicht, a moody jazz-fuelled period short (directed by Anthony Quinn) for LAMDA students graduating next year; and I’m currently working on a second radio play, Male Order (one of a series, Riot Girls, about transgressive women!), and a community engagement project with West Yorkshire Playhouse. So far, I’ve really enjoyed working in radio, where there is a very direct creative relationship between writer, producer/director, and cast in the studio. In 2018, I hope to develop my portfolio further into TV again and film.

What would be your advice to anyone else in a similar caring situation to yourself?

• Don’t try to go it alone. As soon as possible (when you know the situation you’re facing), put some outside help in place, at least as back-up; otherwise, if the person you care for is reliant solely on you, that creates huge pressure and is more likely to result in crisis – specially if you have to work away on location or travel at times.

• If you don’t know where to look for that practical help, approach a signposting organisation – social services, charity, GP, independent consultant, or website. (I’ve collected some useful links on my blog.)

• Identify yourself as a carer to your GP; you may have to do this proactively – ask for a form at reception. Ask your local authority for a Carer’s Assessment. This is now a statutory duty under the Care Act 2014 and should identify your needs, independent of the person you care for, who is entitled to a separate assessment. (There may be a long waiting time, but get the ball rolling).

• Make sure you have applied for any benefits to which you or the person you care for may be entitled. If a person has demonstrable care needs above a certain number of hours per week, you can apply for Attendance Allowance on their behalf, even if they lack capacity to participate in the application (e.g. if they have advanced dementia). Attendance Allowance is not means tested, so you don’t have to delve into the person’s financial affairs or worry about home ownership disqualifying them; and if they are awarded this monthly benefit, you can also apply for Carer’s Allowance, if you meet the other income criteria.

• If you have any kind of staff job, don’t give it up! Go part-time, if you must, but stay on the pay roll to maintain a separate work identity and financial toe-hold and to keep up visibility in the business.

• If you can afford it or get it on the NHS, go for counselling. (Training establishments offer discount private rates.) It helps to offload your feelings to a neutral person.

• Once you have some external help in place, ring-fence time for yourself (both work and social life) and don’t feel guilty about it. Easier said than done, but remember that caring can extend over many years, decades even - and the progression is unpredictable. In the early stages, you may feel you have to put everything on hold for the person you care for; but you need to maintain your own independence, in order to support both of you in the long term.

• Look after your own health! I have just been diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes, which I’m sure is the result of these years of caring and the consequent disruption to lifestyle (plus the stresses of working in TV!) – poor diet, irregular exercise and sleep patterns, comfort eating and drinking.

Why are women disproportionately affected in regards to caring?

Despite women making greater inroads in the workplace, men have not generally made the corresponding change to take on significantly greater domestic responsibility. Where there are children or elderly relatives, it still mostly falls to the woman in a couple to be the principal carer, not least because men are perceived to have more earning power and women more naturally to go part-time or to adopt “flexible”, e.g. lesser-paid jobs.

“Why” is a big question, but I believe a major reason for the government’s under-investment in social care...

“Why” is a big question, but I believe a major reason for the government’s under-investment in social care (which would support everyone of any sex) is the fact that it principally affects women, both giving and receiving care. Care is underestimated (in terms of impact) and undervalued (in terms of status and reward).

I’ve discussed this at some length in my blog post, ‘Socialcare: a Women’s Issue?’

For more from Ming, visit her blog: www.dementiajustaintsexy.blogspot.co.uk

And for more information about parents and carers in the UK film and television industry, and how to effect change, visit: www.raisingfilms.com